Do you have teacher envy?

Do you look over into the other classroom, and as you walk by, you see a teacher smiling, students gathering around desks working together, and creating fantastic projects in their classroom. Do you think, how can they do all of this? What do they have that I don’t have?

Great teachers have self-awareness of what works for them as a teacher and what doesn’t. They know what comes easy for them and can manage the challenges. Great teachers know their strengths!

I taught for over ten years in a middle and high school science classroom. In my first couple of years of teaching, I would watch veteran teachers and believe that I had to teach just the same way. I often would learn new tools to add to my toolbox of strategies. However, when a method that I tried repeatedly didn’t work with students, I felt awkward and very uncomfortable in front of the class. I am sure the students could feel that too! I now see that I wasn’t teaching in a way that fit my strengths.

What has helped good teachers become great is being aware of their strengths. When they know their strengths, teachers can see their students’ strengths to build a classroom that honors diversity.

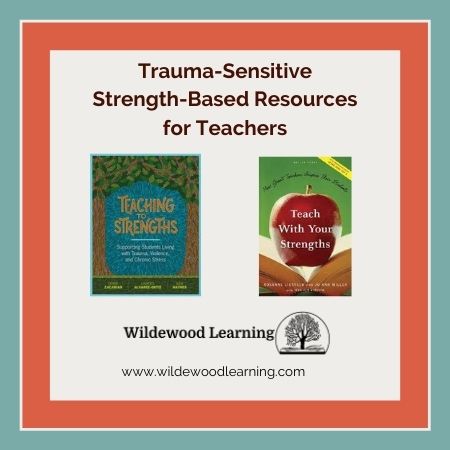

Two resources to help you create classrooms that develop strengths and honor diversity

Teaching to Strengths, Supporting Students Living with Trauma, Violence, and Chronic Stress by Debbie Zacarian, Lourdes Alvarez-Ortiz, and Judie Haynes

Classroom educators have the job of being one of the leading influencers on how a child views themselves and develop their unique set of assets and strengths. Teach to Strengths is written by three English Language Learner (ELL) instructors that approach the instruction of a diverse group of learners from a trauma-sensitive strength-based approach. As stated in the book’s introduction, the fastest-growing segment of U.S. school students is English learners, many of whom have experienced trauma, violence, and stress in very distinct ways. These learners come to the classroom with many unacknowledged strengths and resilience. The authors use case studies and many examples to help educators develop the strategies and skills for creating a strength-based inclusive classroom that capitalizes on the asset of the learner.

This book offers ways to bring strength-based approaches into the classroom, families, schools, and community. A strength-based approach to supporting students with trauma, such as EL learners, can be a way to help educators to see their strengths and values that helped them through adversity and build resilience. When classroom teachers can recognize students, who have suffered adverse situations, they have strengths that have helped them create resilience. We need to acknowledge that the flip side to trauma is resilience.

The teacher-student relationship is one of the most significant influences on student engagement and achievement. As stated in Teaching to Strengths, “the power of our influence in our interactions with students and the methods we use have a great deal of significance in student outcomes.”

The first step is to identify your strengths and values as a classroom teacher. “Our strengths, our assets, and our capacities to support our own well-being and that of others are based on our own uniqueness.”

If you are not familiar with your strengths, I would like to suggest the following books as excellent resources.

Teach With Your Strengths, How Great Teachers Inspire Their Students by Rosanne Liesveld and Jo Ann Miller with Jennifer Robison

Teach With Your Strengths is specifically written for the classroom teacher to know and develop their unique strengths. Teach With Your Strengths uses the Clifton StrengthFinder assessment to help teachers acknowledge their strengths and relate them to teaching strategies that can best help them be better teachers.

The book starts with what makes a great teacher. “Great teachers’ methods and intuitions are different. They don’t operate like other teachers, and they don’t believe everything they are taught or told.” In other words, great teachers know their strengths and weaknesses. They have developed their strengths to create successful relationships with their students. They have also developed successful systems to manage their weaknesses.

The first step in your journey is being aware of your strengths. The book comes with a code to the Clifton StrengthFinder so teachers can start by identifying their top five strengths. If you would like to know all 34 of your strengths in order, you can go to the website and pay a fee to access all 34 strengths and many resources to help you go deeper into each strength. Teach With Your Strengths ends the book with supporting teachers. The rest of the journey is learning to own and apply them in your professional and personal life.

Self-awareness has been a huge part of my journey as a lifelong learner. I have used the process of identifying, developing, and applying my strengths and value to become a better speaker, trainer, and coach. If you would like more support in identifying and using your strengths in your classroom, book a call with me, and we can talk further.